I had always liked wood. Much of our house and many of my favourite play things (e.g., wagon, toboggan, hockey stick, baseball bat, bows and arrows, popsicle sticks) were made of this stuff, in the era before the reign of plastics, aluminum and carbon fibre.

I remember strolling into the large Industrial Arts room for the first time with classmates at CCHS, and being impressed with the rows of carpentry benches, vices, racks of neat-looking tools, and the spray booth from which emanated some rather strange smells. Absolutely nothing was out of place and every surface was clean – rather surprising considering the daily generation of wood shavings and dust.

While some students believed that this course was an easy ride, that idea soon dissipated when our teacher Mr. Leonard Orr entered the room, called the class to order, reviewed what we were going to do before the end of the term, and what he expected from each and every one of us. Little did I know that this quiet-spoken gentleman, with a highly respectable and confident demeanour, would be the most-influential teacher I would ever have through my many years in school and university. If he taught me nothing else, it must surely have been the great importance of accuracy, and of accepting nothing substandard. I soon found myself developing a kinship with him; perhaps in some way he served as a pseudo father-figure, since my Dad had passed away at a young age.

From tie rack, to storage box, and on to many other projects, we learned about grain and other characteristics of different woods, concepts like measuring accurately (measuring twice, cutting once), building useful items with our hands, and appreciating the beauty of each piece once we had almost achieved perfection in our work. Mr. Orr checked each student's progress repeatedly, and gave advice on how to improve it, and encouraged us to do better next time. Some of the pieces he finished with a coat of lacquer, and then gave us our grade. An A or B really meant something, since his standards were high. His Industrial Arts class demonstrated more than simply working with wood and tool safety; along with his Biology class, we learned the excitement of creating with our hands, and the intense pleasure of learning, while building confidence and developing our powers of close observation – all attributes that I am sure helped lead me into a career as a scientist.

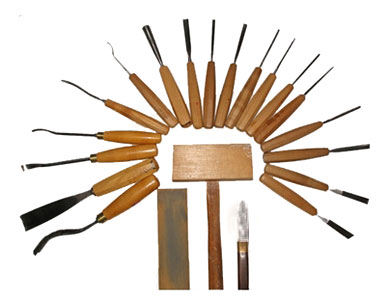

It seemed only natural then that I became fascinated with wood carving and wood sculpture (strangely, cabinetry never appealed to me), and in this field, there was no better place to pursue this traditional craft than in Quebec. In the local shops and churches of St. Lambert and Montreal, one could always find wood carvings – some generated for the souvenir trade, but others wonderful creations of masterful three-dimensional sculptures or low-relief plaques. I tried carving little animals, as I remembered an elderly gentleman on Maple Avenue, who would carve a little Scotty dog in pine in minutes while waiting on the corner of Desaulnier Boulevard and Oak Avenue for the next morning street car, and then offer it to some child (including me) that showed interest in its execution. I began lingering around Ranger and St. Lambert Hardware stores on Victoria Avenue, examining chisels and pieces of lumber. I bought woodcarving books containing techniques and patterns, and as I chiselled away, my projects became ever-more complicated. I soon needed some real wood-carving tools – ones of different sizes, shapes, and angles, to chisel and gouge out those hard-to-reach places (e.g., under-cutting). To search for these items (before the days of computers and the internet), I took the bus to Montreal and wandered through several stores that catered to woodcarvers, and over the years I accumulated quite a variety of high-quality Henckels Twin-brand German chisels and gouges, for every type of cut.

Most of these tools would now cost $30 to $80 each to replace. I kept them razor sharp by rubbing them carefully against a special oilstone, and the metal parts oiled to deter rust. It was important to keep them in excellent condition.

Several years later, when my transportation mode graduated to a car, I had occasion to travel along the south shore of the St. Lawrence River to the Gaspe with my St. Lambert sweetheart, Gail Trueman, and we stopped in a number of small towns to visit shops that specialized in basswood and oak carvings and plaques. Foremost was the small town of St-Jean-Port-Joli, where it seemed half the carvers in Quebec had their studios. It was an exciting experience to observe and to talk to these artists while they worked, and I was enthralled at the large bas-reliefs that pictured entire scenes with people, houses, streets, and farm fields, designed and carved so skilfully in three-dimensions that they were filled with life and charm.

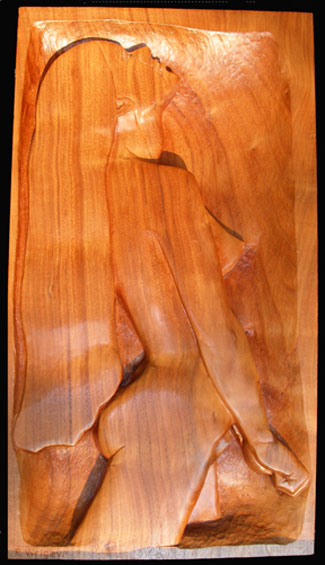

For several years while attending high school, I managed to turn out a variety of small pieces – a hill-billy figure in pine, mushrooms and mice in teak, a mahogany whale, and a figure in walnut.

The Hillbilly in White Pine is 19cm high.

The Teak Mushroom is 20x12cm.

The Nude in Walnut 60x32cm.

Sadly, I had little time to pursue carving seriously through university years at McGill and Illinois, and then was kept busy starting a career and family in Winnipeg, but I never entirely lost the desire to carve wood. I found it so pleasing to feel and hear the gouge or knife slice through the wood at just the right angle with the grain. Some woods like teak gave off a wonderfully fragrant aroma with new exposure to the air, and walnut and ebony took on such a beautiful high polish when sanded and oiled. Eventually I found time to work on some large pieces, and the incessant pounding rhythm of a mallet and the appearance of wood chips throughout the house tested the patience of my wife. Having memorized all the human bones and muscles while in high school, and taken pre-med courses at McGill, I found the human figure fascinating, so I naturally gravitated to sculpting human figures. Being a male, I found the female form more intriguing, although I had to resort to pictures instead of real nude models. Some of these attempts (fully anatomically correct of course, with no fig leaf in sight) still hang on the walls of my home. For years I hoarded prize pieces of lumber in my basement, where many still remain, awaiting a time when I can devote some uninterrupted quality time to my old hobby.

An occasional trip to the coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island provided ample inspiration for carving, with striking cedar totem poles, dramatic masks and utensils present in every museum and art gallery. Other favourite design topics included animal life, reflecting my fascination with Nature.

The Teak Egyptian Lioness is 92x35cm.

My most-ambitious project was copying a famous scene of King Ashurnasirpal II, Hunting the Lion; Assyrian, 880 BC, found at the Royal Palace ruins at Nineveh (on the Tigris River, now south of Mosul, Iraq). For me, this image from a book on Assyrian sculpture captured the essential nature of humanity, ever struggling to dominate the world. The King, riding in his chariot pulled by three horses, shoots arrows into an attacking lion, urged into pouncing by three soldiers banging drums. The scene bursts forth with tremendous action and energy, with rippling muscles of the lions and horses. It demonstrates for all ages this King's power, and his desire to protect his people and possessions from all dangers.

To begin this remarkable scene, I edge-laminated four wide boards of teak (each specially selected at a local lumber store specializing in exotic hardwoods) into a large panel measuring 7 feet x 3.5 feet x 2.5 inches. I then transferred the scene onto the panel by using the method of squares, and set to cutting out the figures and background. While initial progress was swift, working on the fine details (up to five different levels, each undercut to create a 3-dimensional illusion) required a delicate touch, patience and time, since once removed, wood could not be replaced (and was therefore more challenging than sculpting modeling clay).

The Teak Assyrian King plaque (with me in front) is 214x107x6cm.

Still working on the project (while Director of the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature), I had a wonderful opportunity, by means of a British Council Grant, to study museums, art galleries, zoos and botanical gardens for two weeks in the United Kingdom. In the bowels of the British Museum, I eventually found (with the help of a staff member) the original limestone plaque of King Ashurnasirpal. I was struck by the great beauty, balance and grandeur of the piece, executed in limestone, and remarkably about the same size as my panel, but in only a half-inch in relief. I just sat there in astonishment in front of my favourite piece of art, and admired the skill of these early artists. It was one of those exciting discoveries and moments I will never forget. I now wonder whether I would have come to appreciate sculpture so much without my earlier training back in high school. Those few years in Industrial Arts class opened up the world of art for me.

My old Industrial Arts and Biology teacher, Mr. Orr, has long-since retired as a teacher and principle, but still lives on the South Shore, and it was a marvellous moment for me and fellow student Brita Housez (formerly Stolz) to see and to talk to him in the high school Library during the 2005 Reunion. The occasion reminded me of the influence our favourite teachers had on our lives, and their dedication over their long careers to hundreds of students that flowed through their classes. As a gesture of deep appreciation and friendship, Brita and I continue to send Mr. Orr a copy of each new book we publish, and I know he is proud of two of his favourite students. I will have to send him pictures of my Assyrian bas-relief someday when I have finished it. Perhaps he might even reward me with an 'A' this time.