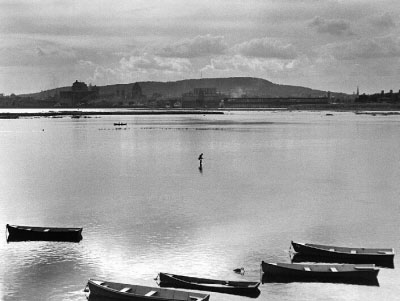

I'm the little twerp far left with the very strange bathing suit. I wonder how my mother allowed me to appear in public like that. - Heather

To reach the public beach, where Argyle met Riverside Drive, I had to descend a set of stairs cut through a massive concrete wall built to prevent flooding in the spring. The beach, if it can be called that, was an extended slab of concrete that ran from the base of the wall thirty yards or so into the shallow water. From this base an ingenious combination of logs, linked by chain and catwalks mounted on sawhorses, extended our swimming area farther into the river. Large rocks held the sawhorses in place. Where the water was deeper, wood planks were installed to divert the current. This provided a safe area where you could, if you chose, swim and avoid the current. Beyond the catwalk was a raft, floating on barrels and anchored to the bottom with chains and cement blocks. To get to the raft, we had to leave the safety of an enclosed area and swim across a few feet where the current was strong. A diving board was mounted on the raft. Although it was forbidden, one of the "dares" we undertook daily was to dive from the board and swim underwater with the current beneath the raft, bob to the surface and head back upstream to the raft.

One of the benefits of learning to swim in a river where the current was strong is that it produced strong swimmers. The kids from St. Lambert regularly beat out competing teams from Montreal because their training was confined to pools. Our main rivalry came from members of our own team. I was a water rat. I learned to swim when I was eight and from then on I spent the better of part of each summer day, rain or shine, at the beach. My mother would pack me a lunch and I'd bike there, leave my bicycle in a rack, unlocked. There were changing rooms on the concrete beach and our clothes were stored in rows of open boxes facing the water. We were warned to make sure these contained no money or valuables, but the warning was often ignored. I don't recall anyone reporting anything being stolen. And my bike was always where I left it when it was time to return home.

The two lifeguards I remember from my years in St. Lambert were Bob Gravel and Butch Duschene. They “policed” the beach, warning against running on the catwalks or pushing people into the water. Violators were banned for a day or two. Second offenders might be sentenced to a week or more. Occasionally the lifeguards would venture out to “save” swimmers in trouble. These were usually people unfamiliar with the current and the saving simply involved guiding them downstream, with the current, into shallow waters where they could then walk back to the beach.

Although it was also forbidden, the better swimmers often left the relative safety of the beach, and headed downstream to a stretch of water known as the sluices. The sluices, where Victoria Avenue met Riverside Drive, had once been the site of a railway line that stretched to Moffat's Island, about a mile into the river. From the island people could take a ferry to Montreal. When the Victoria Bridge was completed, the need for this means of transportation was no longer required and the railway line was destroyed, leaving white water rapids that ran over the remaining debris. We soon learned that by floating, face down, we could “shoot” these rapids without any real danger. It looked frightening to anyone unfamiliar with the process, but there was enough water running over the debris to ensure safe passage. It was a mistake to try to swim through these rapids, because this could produce nasty scrapes to the knees, elbows and stomach. Once through the rapids, however, the water was deeper and the current unpredictable, a fact I found both more exciting and more fun.

On a few occasions when a lifeguard caught me diving under the raft or heading for the sluices, I would be banned from the beach for a week. This didn't keep me out of the water, however, because I simply headed down Sanford Avenue, a mile or so downstream from the beach and a few blocks from my home. There I descended fifty feet of rough terrain to the water's edge. And while the current here was strong, the water was shallow and it was possible, if I picked my way carefully, to walk a hundred yards or more out into the river itself. The bottom was smooth rock and the water clear enough for me to see a fish swimming.

These were the days before anyone worried about skin cancer and by the end of the summer you could always tell the swimmers from the non-swimmers. We swimmers had tans that were considered cool, the darker the better. But no one's tan came close to that acquired each summer by one lifeguard, Bob Gravel. He was, quite simply, black. Of course he was dark to begin with and had a decided edge over those fair skinned rivals. Butch, his successor, was a far better swimmer than Bob, but never attained the same dark tan.

To grow up in this setting was something I took for granted. It was only when I visited relatives in the States that I would be reminded how lucky I was. When cousins asked, “How far can you swim?” I would shake my head. “How far can you walk?” would be my reply. Swimming for those of us who loved it was as natural as walking. You swam the St. Lawrence in the morning, afternoon and evening. It was what you did. Distance was irrelevant.

Today, when I look out over the vast track of parkland that once was open water, I see they've built a swimming pool for the local kids. They probably think it is terrific fun to spend the day there, swimming in chlorinated water, running, and pushing each other in. And the lifeguards probably blow their whistles to stop the horseplay. But those lifeguards don't have the tans to match our lifeguards. Perhaps that is just a well. But sadly, those kids no longer have the St. Lawrence River to explore. They don't know what they are missing, but I do and I feel sorry for them.