“To play billiards well is the sign of a ill-spent youth.”

Herbert Spencer, 19th century English philosopher.

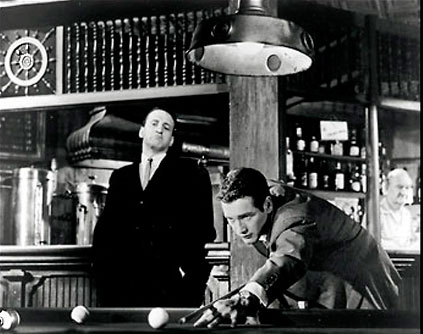

The dark interior was illuminated by glowing expanses of green felt. There was a hushed silence to the place. The only sounds - the sharp click of ball hitting ball, the distinctive thud when one of those balls landed squarely in a pocket and, of course, the occasional curse. Smoke hung in the air like incense in a church. In fact, the pool hall had the feel of a sanctuary. It was an all-male domain with no girls to distract you and no parents or teachers to impose rules. In the B movies we liked, pool halls were inevitably frequented by bad guys planning crimes or making illegal bets. So there was something vaguely disreputable about the place to begin with.

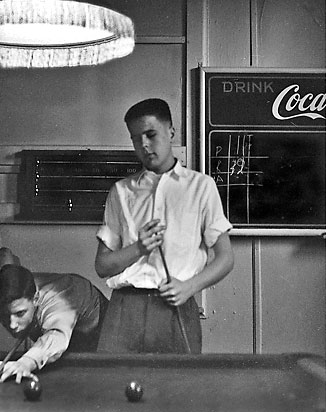

In St. Lambert it was where we went when we played hooky. In short, it was the perfect place for a rebellious adolescent to hang out. And hang out I did – enduring the inevitable hazing as I gradually learned to play the game. Eventually I became reasonably proficient. Never a shark, just a decent player.

Alan Walker takes careful aim while Gerry O'Connor (both C'53) looks on.

I never learned the name of a silent, middle-aged man with scarred face. He refused to remove his sunglasses or his pork pie fedora. The list goes on. These evening players placed bets and the stakes could run into the hundreds of dollars. We rarely bet on our games and when we did, a quarter was the usual limit.

Most of my friends kept word of their pool-playing prowess from their parents. But when my father learned I'd taken up the game he wasn't alarmed. He reminded me his father had run a pool hall in Leamington, Ontario. It was, he said, an honorable profession. It had paid for his university education. And this brings me to the rather unhappy conclusion to this tale.

The summer when I was fifteen we spent part of our vacation visiting my grandparents in Leamington, Ontario. My grandfather had retired, but his old pool hall was still open. My father suggested a friendly game of snooker. I was more than happy to oblige, anxious to show off my skill. We walked downtown to the poolroom and booked a table. My father had played the game in his youth, but it had been years since he'd chalked a cue. And it showed. Without thinking it through I went about soundly trouncing him. Not a smart move.

As we made our way home the discussion turned to the rather disappointing marks I'd received in school that year. I'd passed, but by the skin of my teeth.

“Maybe,” my father said, “you might improve those marks if you spent a little less time in the pool hall.”

Then he quoted Spencer.

“To play billiards well is the sign of a ill-spent youth.”

Andrew Clyde Little