I sympathize with today’s students, unable to cover their major educational costs by working summer jobs, as I and many of my fellow Chambly County High School graduates were able to do. I chuckle when I think back to those summers, when I was prepared to do just about anything for money to buy books and to pay for relatively inexpensive courses. Residing in St. Lambert, I was fortunate in being able to commute to McGill for six years by bus, or car pool with friends, so my living and transportation costs were low.

My first two real summer jobs while attending CCHS were with the City of St. Lambert, where I learned the fine art of painting crosswalks on streets with a brush, while sitting on the paint can. One had to keep alert, since cars passed rather close by. My companion made the inexcusable mistake of knocking over a full gallon of yellow paint on the freshly asphalted parking lot at the St. Lawrence Park pool. We spread the thick liquid between the two parallel guidelines, hoping that our handiwork would be seen as a parking spot reserved for really important persons. Our supervisor took another interpretation and was not amused.

I was then transferred to a tree-trimming crew and learned the perils of cutting down huge limbs, and the importance of keeping one’s feet clear of tangled brush. One morning I was handed an old-fashioned, five-foot-long scythe (before the gas-powered lawn mower was readily available) and instructed to cut grass and weeds in vacant lots. How many of today’s students could say they have mastered this ancient skill? There was something most satisfying in repeatedly swinging the handle in a wide arc and watching the sharp curved blade cut cleanly through the wall of vegetation. Okay, it was harder than it looked, especially when the blade came into contact with an unforeseen rock, with bone-jarring effect. With aching arms and back, I had to take frequent breaks, but I kept looking busy by touching up the blade edge with an oil stone.

The worst of my duties that summer was working behind a smelly asphalt truck, shoveling and packing hot asphalt into potholes under the merciless heat and humidity typical of a mid-summer day in St. Lambert. Towards the end of summer, I was relocated to help another crew that was loading discarded appliances and brush into a big truck for disposal at the dump. My public-works career (and life) almost came to a sudden end when the rusty pipe atop a heavy water heater, which I was hoisting up, broke off in my hands as I was perched atop the truck, and I catapulted backward into the street. Fortunately there were no cars passing by at that moment, and my cat-like instinct (perhaps tuned from playing sports) came into play and I was able to twist and land on my feet without damage, two metres below on the pavement.

The following summer I was offered a safer position as a playground leader at Logan Park, and the biggest challenge was attracting kids in the neighborhood by means of innovative play activities. I remember Mr. Eric Sharp (Director of St. Lambert’s Recreation Department for 29 years, and Mayor from 1986-90) driving up in his black car to check on the day’s activities, and to make programming suggestions. With each summer’s paychecks stored safely in the Toronto Dominion Bank on Victoria Street, I was well on the way to financing my first year at McGill.

The next summer I was having a hard time lining up a summer job, so as a last resort, I I started at one end of Saint Catherine Street in Montreal and went from store to store, enquiring if they were looking for help. One after another sympathetic owner or manager told me that no temporary positions were available at the time. Fortunately, a great neighbor on Logan Street, Mr. Robert Smiley (who became Mayor of St. Lambert in 1974), heard of my predicament and kindly offered me work at his Montreal chemical company, H.L. Blatchford Ltd. Here I learned much about chemistry, particularly urethane-foam insulation, which was then in the experimental stage. We used the halocarbon freon to generate the bubbles in the foam -- a chemical that was also used widely as a refrigerant, but which was subsequently banned due its ozone-depleting properties in the atmosphere. It was fun spraying the urethane mixture onto a test wall and watch it foam up. I particularly liked using amyl acetate in other formulations, as it had the most-tantalizingly sweet odor (hence its use in manufacturing candies, but is also added to paints). I was shocked to see an older employee routinely wash his hands in the toxic solvent toluene. Thereafter, I made a greater effort to learn about dangerous chemicals.

Continuing in the same vein of chemistry the following summer, my new position was research technician at Ogilvie Flour Mills in Montreal. My main task was to test the strength of various corn-starch formulae in relation to the manufacture of corrugated cardboard. The equipment used to separate the cardboard layers accidentally grabbed a colleague’s lab-coat sleeve, and almost pulled him into the rollers. After seeing his torn coat and shaken state, I was more careful around all the machines. My close friend and former CCHS student Bruce Lauer was working next door on dough elasticity by incorporating various concentrations of gluten. He demonstrated one test for me in which a ball of dough literally bounced off the wall like a rubber ball. A welcome perk of our employment that summer was being asked by the female kitchen staff to taste-test various cakes each week, and we were allowed to take home samples on a regular basis. At lunch time, Bruce and I liked to ride the primitive elevator (a small circular platform that rose up through holes in each of 20 floors) to the top of the grain elevator, providing a great view of St. Lambert and Longueuil across the St. Lawrence River.

My next year’s position was as a research assistant for a PhD student at Redpath Museum at McGill, who was studying rare songbirds at McGill’s Mount St. Hilaire Field Station. This extensive property of forest, meadow and lake was a budding biologist’s dream environment. The mature beech-maple forest and rocky hillsides were filled with wildlife, and I spent many a happy day wandering through the forest, identifying songs of the cerulean warbler, veery, and other birds. Using a shotgun with fine shot, I was instructed to collect certain species for the Museum, and I was taught how to prepare bird and mammal specimens for the research and display collections. I attempted to conduct a small-mammal study by setting live-traps in a quadrat, but my project came to a sudden halt the following morning when the local raccoons took advantage of the peanut butter bait and the mice in the traps. I guess I failed to take into account all the variables of the site; another important lesson.

While at the Redpath Museum one day, a Montreal exotic dancer was referred to me for health advice on her ailing pet boa constrictor (since I happened to have some practical knowledge about snakes), which she handled in her performances. After I examined the snake and provided suggestions, she kindly offered me a special pass to watch her show. I was rather busy with my studies, but later regretted not taking advantage of her intriguing offer.

With more experience under my belt, the ensuing summer I was accepted as a field technician with the Quebec Wildlife Service, with activities centered north of Quebec City in spectacular Parc des Laurentides (now divided into two national parks and a wildlife reserve). My duties were three-fold. I was asked to make a survey of small mammals, participate in a caribou-range survey (by identifying and weighing lichens and other plants) prior to a re-introduction of this species, and to assist a veterinary crew trap moose (for health examinations) and black bears (which were causing trouble in a local village). We anesthetized a large female moose which was trapped in a spruce-pole stockade, and my job, while kneeling down in the thick mud, was to hold its huge head steady so the veterinarian could take blood samples and measurements. Its great dark eyes looked up at me, and its breathing was rapid and deep, revealing the poor animal’s stressed and exhausted state. Suddenly the moose struggled violently and regained its feet, tossing me aside like a stuffed toy. It was an incredible scene of pandemonium, as five trapped crew members scrambled up the 3.5-metre-high walls like monkeys, and the vet and I tried to run in the sucking mud towards the single doorway that remained open. We barely lunged outside and sideways when the groggy moose staggered out like a drunkard, right on our heels. After catching our breath, we all broke out in laughter, hiding the fact that we could have been crushed by this 400-kg cow moose.

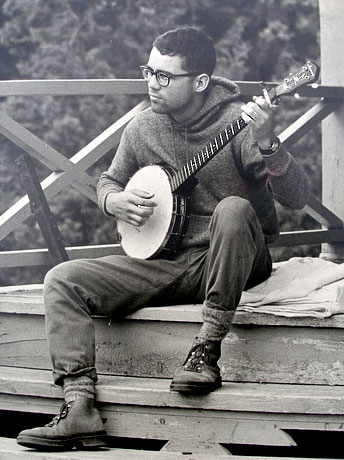

The following week we trapped and relocated a wolf, which was surprisingly docile through the operation of tying its feet to a pole. Then we attended to a subadult black bear which had been trapped on the edge of town. The anesthetized animal was unceremoniously carried out of the bush on the shoulders of a burly technician named Bulduc, and thrust untied into the back of a pickup truck. As we prepared to drive away, the bear suddenly woke up and threatened to come barreling out of the truck right into our faces. An unconcerned Bulduc, who had once had a bear as a pet, stepped up to the snarling animal, and leaning backward, kicked it with full force in the nose, knocking it unconscious again. The bear was restrained this time and eventually released relatively unharmed in its new location, far from people. Not a technique found in wildlife-management manuals, but it sure worked. During leisure hours in the evening, I played my banjo and went fishing for brook trout. On some weekends, I was able to take home fresh fillets to my girlfriend Gail Trueman at her cottage in South Bolton in the Eastern Townships, a 350-km drive south.

Robert enjoying some free time while stationed in Parc des Laurentides, Quebec, in 1962.

Another summer I landed a prime position as a mammalogy technician at the National Museum of Canada in Ottawa. Ever since I was a child growing up in Buenos Aires and St. Lambert, I loved the outdoors and visits to museums and zoos. Having the rare opportunity to learn more zoology at two major Canadian museums was instrumental in my giving up an original plan to become a surgeon, and to pursue my nature-related interests towards a full-time career. At the National, I met many well-known curators such as Earl Godfrey (who authored the classic Birds of Canada), and Museum Director Frank Banfield (The Mammals of Canada). I felt it a great honor to be working at the same grand institution as these Canadian pioneers in natural history.

At the University of Illinois, I taught in zoology labs but concentrated on courses and my thesis in mammalogy (the study of furred animals). I traveled in summers from the Maritimes to the southern Appalachians to collect specimens in the field and to record data in a number of major museums in the USA and Canada. Just before my final year at Illinois, I received a letter from the National Museum of Canada Mammalogy Department, inviting me to lead a two-month expedition to the Northwest and Yukon territories. In spite of my professor’s reservations, I felt it was just too-great an opportunity to miss -- conducting wildlife research in the Arctic. So I said goodbye to my understanding wife Gail and my mother in St. Lambert and flew north. Every week my companion and I traveled by float plane or helicopter to a new remote site in order to investigate specific wildlife species, including the Arctic ground squirrel, hoary marmot, singing vole, brown lemming, and other species. From Tuktoyaktuk and Inuvik to Dawson and the Canol Pipeline Road in the Mackenzie Mountains, we camped in breath-taking landscapes from sea level to high mountain peaks above treeline. Adventures too numerous to relate flowed by like the mighty Mackenzie River, which we crossed several times. Suffice it to say that we managed by sheer luck to survive close encounters with black and grizzly bears, a forest fire, fierce storms, and malfunctioning and out-of-fuel aircraft. I made myself a promise to never again fly in a small plane (Over the years, four biologist friends died tragically in separate small-plane and helicopter crashes).

As I graduated with my PhD degree in 1970, my university days, as well as the succession of summer positions, came to an end, and I accepted a full-time position as Curator of Birds and Mammals at the new Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature in Winnipeg. Now retired, I still like to reminisce about all the learning opportunities and outdoor adventures afforded to me as a student by so many thoughtful people, including several of my professors. I cherish these memories and value life-lessons learned, such as teamwork, persistence, patience, and the ability to over-come challenging working conditions.

Fifty-three years later, Robert still heads out into natural areas at every opportunity to pursue his research interests in entomology. (Photo by Ron Boily)

I now volunteer as a Board member and Chair of a science committee for the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Manitoba Region, and I see summer-student interns heading out to conduct field activities with new knowledge, computers, GPS, and other sophisticated equipment. It is gratifying to know that lucky and enthusiastic young people are carrying on the great tradition of gaining practical experience and funds to help cover their educational costs by working summer jobs. It’s an exciting time in one’s young life.