After a couple of unsuccessful attempts to get me to move one foot in front of the other, my mother, a talented athlete all her life, glided off around the rink, her fitted Norwegian sweater, jodhpur ski pants and graceful gliding style attracting the attention of all of the males on the rink.

In that beautiful but humiliating moment, my relationship to sports was set for life. With one and a half exceptions, I remain an incompetent, hapless observer of other people's athletic prowess. I have tried quite a few sports, I have never given up trying new ones, but the results have been almost uniformly without productive result.

1950: Me, mummified in the snow suit, minus the cheese cutters but already on my first job shovelling snow at my grandparents on Maple Ave.

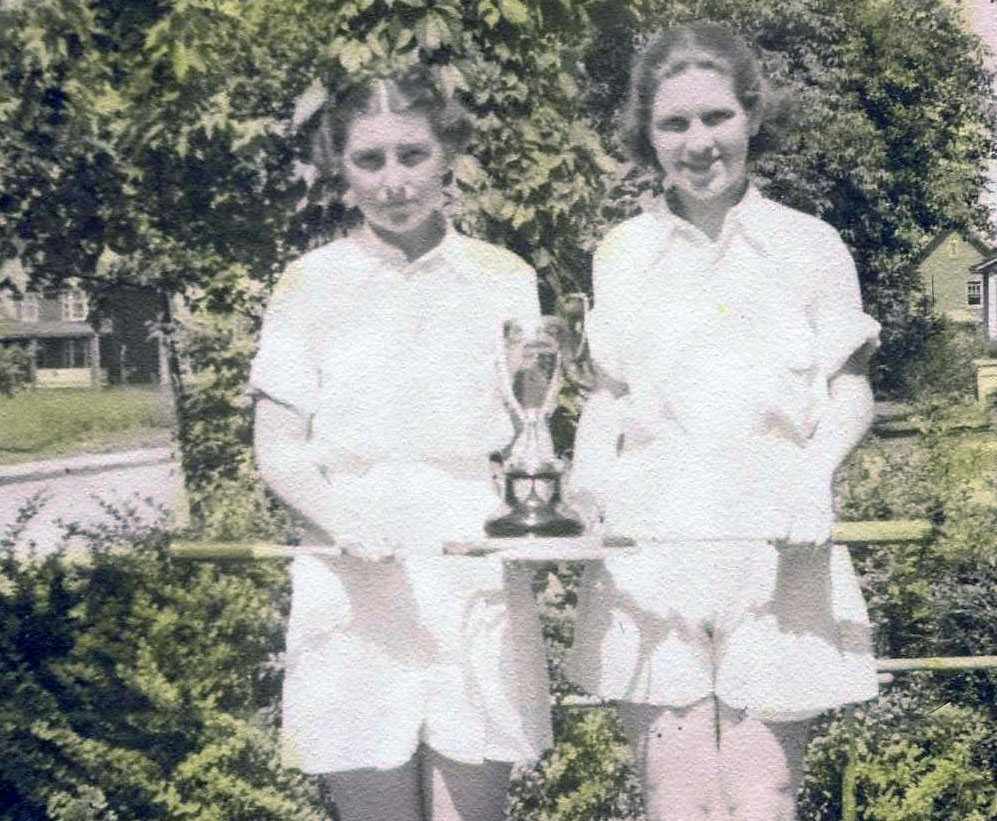

And there really was no excuse. My grandfather, Fred Thomas of Maple Avenue, had been a successful long distance runner; his daughter, my mother, swam, skied, skated and regularly won tennis trophies. And in the fifties and sixties, St. Lambert became a sports paradise, a snowbound Australia or Cuba, but without the sun or rum, cigars or the beaches. Residents were eager to invest in young athletes (mostly male unfortunately), ready to volunteer as coaches or to contribute personal funds for a new rink or wading pool, all under the leadership of Eric Sharpe, and Doogie Parsons -- successive heads of the Community Sports Association and very energetic, wallet-squeezing fund-raisers.

So where did I go wrong? I think my main problem was my reticent personality but I also blame the march of technology and the St. Lambert Library.

Those who remember me from Victoria Park (my athletic "home park") and from CCHS will recall my shy, retiring personality, quite lacking in the robust exuberance which normally attends the male species. I was quiet and soft spoken, a shrinking personality which grew smaller with every athletic setback. In behind a humble exterior, lurked a very confused person, constantly humiliated by his failure to grasp the concept, especially on the jousting fields of athletic endeavour.

At my first Sunday school picnic, we four year olds were lined up at the starting line of a race track, probably L'Esperance again. A gun went off, parents shouted, and kids scattered, stumbling like parts of a shattered crab toward the finish line. Eventually, I got the idea and dashed from behind to finish a scintillating sixteenth in a field of....fifteen kids. Afterwards, winners pressed forward to the prize table to collect their medals and cups. Like others who had won first, second or third place, I picked up a large blue box from the table as "my" prize. After an angry struggle with a large purple-faced official, my mother dragged me away and explained in her quiet but direct way that: "losers don't get prizes". An imprint of personal inadequacy was established, another psychic scab for my collection of emotional wounds.

Caption: 1933: Dorothy McNeish (Thomas), SLHS 1939, with unknown friend and tennis trophy in front of Dorothy's house at 328 Maple Ave.

Opportunities for sports multiplied along with the network of new facilities all over town. The first winter we moved onto Union Boulevard, up the street eager fathers packed snow, watered and smoothed it, then erected a rudimentary hut which would serve as a headquarters for "generals" during snow ball fights, the penalty box during hockey games, and a protective wind break for changing from boots to skates.

January 1955, My brother, the athlete, on the ice our first winter in Victoria Park - note the absence of “boards”

Over the years, a telephone pole was erected for playing Danube waltzes for the “girls' figure-skating period” and the hut morphed into the “shack”, a substantial building with washrooms for boys and girls, and heat in the winter -- all presided over by a suspect, transient figure called Earl or Bill. At the top of the field, a baseball backstop and gravel diamond were set up, and playground equipment erected. At other parks around town similar infrastructure was established or improved, including the luxury of a wading pool at some, or stands for spectators -- especially GIRLS -- to witness the gladiators in action. In the sixties, a municipal swimming pool was opened and later, a track and field facility which together formed “Seaway Park”.

Unfortunately, the excellent facilities did not foster the necessary skills to ease my bewilderment on the field or ice. Each season, my mother signed me up for the organised sport-du-saison and got me the coloured shirt which identified our team -- normally yellow in the case of Victoria Park. But my nerdy, athletically-challenged father had no skill to impart and no self-respecting boy in those days could accept coaching from his mother. So on the opening day of each season, I arrived at the appointed sporting venue, without a clue what I was doing there, or why. In those days, “coaches” on summer evenings and weekends were mostly fathers just home from work, who patiently tried to explain some basics and keep order among rambunctious kids. During football season, when the days were shorter, teen age coaches shouted incomprehensible orders, and the rest of my team used me a tackling dummy. I made little progress.

Bottom line: organised sports were disastrous for me.

In the summer, I spent most of the baseball season on the bench, playing with the soft dust under my seat. The few times I got to bat, I fluffed the easiest of pitches; in the field I waited until the last minute to realise that the “easy out” fly ball heading directly to me, was about to fall ten feet in front of me or sail ten feet over my head.

Forty years later, as a an important, dignified Canadian diplomat in Havana, nothing had changed. In one of Cuba's largest baseball parks, (thankfully empty of all but a handful of onlookers), a titanic match occurred between “Canadian” and local Embassy staff. All I can remember is a series of strike-outs, no matter how soft the underhand pitches, a monstrous fielding error where the ground ball came straight at me, slowed in the long infield grass as it got close...and dribbled through my legs. And just as in my youth, from the scattered family members in the stands I could hear the soft, mocking laughter from baseball-savvy Cuban onlookers. On my first posting in Kenya, a group of us from the High Commission invited a Japanese policeman who was running a martial arts programme for the Kenyan Police on a camping safari to northern Kenya. Every morning, as the sun rose over the desert plain around Lake Turkana, he practiced his judo “katas”, a poetic marvel of absolutely precise physical and mental self-control. Around his perimeter I would stumble, looking for my glasses and socks while trying to avoid the scorpions and snakes and being hit by his lethal fists.

My brother and his gradually freezing feet are hidden behind the other players. Note the boards are higher and the pole for Danube Waltzes is up. Unknown GIRL watching the action.

Back in St Lambert, the performance of other athletes was a constant affront to my uselessness. One memorable summer evening, someone hit a line streaking drive at shoulder height, about four feet off third base. Nelson Reynolds, playing third base, extended his bare hand, snagged it out of the air, touched third and tossed the ball to second -- a “play of the week” double play to shame any Major League player, and all the more extraordinary because it was accomplished so casually. My own brother was fearless and constantly hounded the coaches: “Put me in coach, I can do it, put me in.” While I seemed to get more inept, he became quite adept at each season's sport. Admittedly, his prowess had a price: one bitter February morning, after fifteen relatively immobile minutes between the goalie posts, he hobbled to the “shack” in his pads, limped over a baseboard heater, and slowly and painfully thawed his frozen feet. But he got right back out there to finish the second half of the game. Men-boys were tough in those days!

In football, I was invariably a guard who had no clue what the “signals” meant, or what I was meant to do once the “signals” launched the “play”. Circumstances repeatedly reinforced the point that I had no business on that field. One sunny autumn Saturday morning, I got to play most of a game, but faced a behemoth who was more concrete wall than human. After my first three or four tries to move him out of the way, we both realised that was not going to happen. As we locked helmets after that, he sent me knowing but not unkindly smirks. I replied with a rueful grimace, signalling: “What can you do? (but please don't hurt me.)”. In winter, I spent most of my first few hockey seasons standing in the snow on the sidelines. That was actually a relief because if I was sent out to skate, my weak ankles dragged so constantly along on the ice that my stretched ligaments were constantly in pain and hampered my desperate efforts to avoid falling down, while using my stick both to hold me upright and to push the puck forward.

As Macbeth once said to the audience (thank you Mr Patterson of Grade Nine English): “Season after season after season, Creeps in this petty pace from day to day, To the last syllable of recorded time, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools, The way to dusty death.” For inevitably, on the sidelines of all my organised sporting events were the crowds of “lighted fools” -- parents, and friends from school -- constant, hooting witnesses to the ineptitude of a wretch who could not hit, or catch or run or skate backwards or turn gracefully by putting one foot over the other -- every smirk and chortle turning my soul into “dusty death”.

1960, another affront - Ian Bourne (left) and Roger Taylor, in yellow Victoria Park jerseys, execute perfect parallel ice-spray stops, just like the Real Hockey players on hockey cards. It's a wonder that I did not join a reclusive holy order in Tibet to avoid the seasonal torture. But that would have meant a huge effort to climb the Himalayas, which was beyond me; and with my luck, I would have encountered Brad Pitt or Richard Gere, dropping in for a spot of Zen meditation and to humiliate me with their beauty.

The one perk of organised sport in St Lambert was the end-of-season father-son banquet to hand out the championship crests to winning teams. Those were my first times attending “grown-up” events, and remain a good memory. Participants sat on chairs along banquet tables. This being the fifties and early sixties, fathers were dressed up in suits and ties, and the kids in their Sunday best. Catering was by Benny's Bar-B-Que, purveyors of what we creatively called “Benny's Barf”. But contrary to the cruel joke, the chicken was perfectly prepared, the soggy fries were flavourful and the bun dipped in Benny's spicy Bar-B-Que sauce is a taste experience that the best restaurants in the world have not equalled for me. The best moment of the evening was when my father watched me - go up to get my crest as a member of a Victoria Park championship team - once each for baseball, hockey, and football. I knew that I had not made much of a contribution to the team's success but I got a small taste of what it felt like to be a winner. The feeling slightly dissipated when my father noticed that I had slobbed indelible bar-b-que sauce on my best jacket or I slipped and fell in the mud on the way out, splitting my best trousers. That taught me humility and modesty in victory, not a useful lesson when athletic success happened so seldom, but failed to dim the glow I felt.

1960, another affront - Ian Bourne (left) and Roger Taylor, in yellow Victoria Park jerseys, execute perfect parallel ice-spray stops, just like the Real Hockey players on hockey cards.

And speaking of chambers of horrors, nine months of every year there was Gym Class. Until Elementary School, there was not much in the way of physical recreation in school except for recess and running home for lunch or after school. But in the dark, oak-floored gym on Green Avenue, we fell into the hands of -- Miss Powell -- a five foot two, running-shoed, black-skirted, white-shirted, silver-bewhistled, shouting terror. Nearly deaf, she embellished the end of each sentence with a singing “nnnnn” sound, as if she forgot to turn off her inner sound button after she finished speaking. And if you got close, you could hear the echoes and whistles from the rudimentary hearing aid she wore. Today, in the light of the journey that women have made to claim their equal place in society, I can admire her courage to face down the prejudice she must have faced as a woman in sports and with a significant handicap. Back then my limited emotional space was fully occupied by constant dread.

Miss Powell had taught my mother, which meant that she must have been in her sixties by the time we met. But she entered each gym class at-speed, brisk with energy. And her voice commanded the immediate attention of every jostling, spotty, pre-teen lout. Every gym session fit the same pattern: first, calisthenics, followed by a “sport” -- gymnastics, volleyball, basketball, and athletics, beginning in the gym during the rainy spring and ending with a “sports day” on a field somewhere (probably L'Esperance; why me Lord?). My role, no matter what the sport, followed the familiar miserable script: if an activity required any combination of strength, agility, coordination or technique, I failed. I couldn't do more than half a push-up (the down half), couldn't climb a rope higher than the first place I grabbed it, could not run AND dribble a basketball, or hit the backboard to sink a layup. One day, having failed to run to a “high-jump” bar, then pick up one foot and the other to complete a scissor jump over the bar, Miss Powell stopped the whole class. She repeatedly lowered the bar until I should have been able to step over it without knocking it over. But I repeatedly failed even to do that -- in front of the whole raucous class. My head hung so low afterwards that, to this day, I can describe every floor board on the route back to my classroom.

At Chambly County, a series of gym coaches followed one after the other in the four years I was there: Mr Williams a gum-chewing (out of sight of other teachers) wiseguy from New Jersey; Mr Augustine, a terse fireplug of a man who looked like Spencer Tracy and played semi-pro football at the new Seaway Park; and finally, Peter Rylander, a CCHS graduate whose toothy grin and wise cracks belied an inner kindness which revealed itself in the patience he sometimes showed for an inept teenager trying to do a somersault (think: a floppy jelly roll on a tilted table) or handstand (think: a 5' 11” CN Tower built from unglued popsicle sticks), or gymnastic moves on the flying rings (think: a cowboy hangman testing a scaffold by dropping sacks of dead sand through a trap door).

I cannot honestly say that any of them imparted much “training”. They assumed that you were strong enough to jump up and grab a pair of rings five feet above your head, pull yourself up, throw your feet over your head, and then circle through without pulling your arms out of their sockets or landing on your head and breaking your neck. (Have I pointed out that men/boys were tough in those days?) On the other hand, the way to become an athlete (is this really a surprise to you all?) would have been to get off my duff and to practice the skills I had not mastered. That did not occur to me until much later -- it still really has not happened.

So who or what can I blame? I put it down to the newfangled television which invaded our home when I was two, and the opening of the new municipal library just off Green Avenue. Why submit myself to the public embarrassment of repeated athletic failure after school, when I could happily join Roy Rogers, the Lone Ranger and Tonto, or the Cisco Kid on their “Happy Trails” to TV adventures? Why humiliate myself on the summer fields of baseball when you could flop on a sunny lawn chair in the back yard and lose yourself in the sleuthing of Sherlock Holmes or the Hardy Boys, the perils of White Fang, Big Red or Black Beauty, or follow the wagons of Alexander the Great, Napoleon or the Red River Carts into danger, triumph or painless (for me) defeat? It was no contest.

And you really cannot say that I did not “participate” in sports. Every Saturday afternoon on our dining room floor in front of the TV, I mimicked tricky wrestling moves on “Grand Prix Wrestling” or “Sur le matelas”, only interrupted when my annoyed father would stick his head in the room and tell me to go outside and find a friend. (If he only knew!) Every Saturday night I sat with tense attention to the fiery speed and finesse of the players of the Club du Hockey les Canadiens, transported to the best seat in the Forum by the excitable Danny Gallivan on Hockey Night in Canada and the incomparably elegant Réné Lecavalier on la Soirée du Hockey. Every spring, when I was supposed to be studying for exams upstairs in the back sun room, I secretly followed the playoff fortunes of le Tricolore -- back when the NHL finished before final exams.

Saturday afternoons, I leapt on the backs of the villains, Killer Kowalski, Yukon Eric, Dick 'The Bulldog' Brower, Maddog Vachon, Eric the Red,and Sweet Daddy Siki. With masterful strength and skill I muscled them into submission. I wriggled out of impossible holds, just like “scientific” wrestling heroes -- the elegant and posh Lord Athol Layton, the graceful Edouard Carpentier (who COULD do somersaults -- and from the swaying top rope), or movie star good-looking Johnny Rougeau. Rougeau reminded me of a French Canadian Charles Atlas, and gave me hope that I could, maybe, one day, transform myself from a flabby, “one hundred pound weakling” into “A New Man!”. I name so many because, without today's makeup, costumes or full-body sculpting and Brazil waxing, each of those hairy, slightly flabby, but talented, athletes projected a unique wrestling persona and managed to make the strict choreography of professional wrestling interesting.

On the TV ice, I was captured by the grace of Jean Beliveau, whose effortless glide regularly harkened to my mother's smooth stride that beautiful spring morning a decade before. I knew I was supposed to look up to the fierce Maurice “Rocket” Richard, and I did get his autograph one summer afternoon at an event at Logan Park. But I preferred his shorter, gritty, brother Henri “Pocket Rocket”, and I could see myself in the seemingly awkward, but ruthlessly effective Doug Harvey, especially since, in Victoria Park, lousy skaters (which he was not) always played defence.

My brother and I in the obligatory Canadiens sweater with tricolore tuque

My heart belonged to the goalies, those solitary, truly heroic men who stood steadfast between two iron pipes facing dozens of frozen bullets launched at their unprotected heads at a hundred miles an hour. I wanted so much to be the iconoclastic Jacques Plante, who dared to knit tuques and socks on the trains between games. A man of few words, “Jake the Snake” alternated slick, sinuous saves in his crease with outrageous meanderings all the way out to centre ice and beyond to chase loose pucks. Famously, he faced down opposition from the whole NHL to insist on wearing a protective mask on his face -- a mask which he designed himself and which dug deep into the psyches of his opponents, scaring them out of scoring goals -- Friday the Thirteenth, indeed. And again, he did not need the outrageous paint jobs, monstrous armour or attention-seeking flip-flopping of modern goalies -- just a bottomless stare and quick, perfectly timed flicks of a pad or stick.

But the embodiment of my personal dreams, and inspiration for a short spurt of personal sporting madness, was Gump Worsley. A short, pot-bellied advertisement for the beer he drank to excess and the exercise he never bothered to do, Worsley flopped and floundered his way to a Stanley Cup, while remaining one of the last goalies not to wear a mask. Inspired by Worsley's (bad) example and the coolness of being a goaltender, in my final winters of high school I went to the rink every afternoon. In borrowed pads, a baseball catcher's mask and first baseman's glove I attempted the slip-sliding moves of my heroes. Unfortunately my style was in reality a flip-flopping disaster. Finally, late one afternoon a father and old son arrived on the ice while I was still skating in my equipment after everyone else had gone home. The little four year old skated end-to-end, came straight at me, deked, and put the puck right between my legs, flat on the ice, a slow-motion horror of a goal. Leaving the choked laughter of the father behind me, I skated off the ice, took off the pads and strode silently into retirement.

After all this, it seems incumbent upon me to draw important lessons to share with your nieces and nephews and grandchildren -- especially the teenagers who will be eager to hear about sex. Yes, you read right. After a lifetime of physical inactivity, I now realise, too late, that my lack of athleticism is the reason why the sexual revolution of the sixties passed me by and left me a fat, bald, sixty-five year old, bachelor virgin. Dear readers, tell your teenagers: if they have not mastered any moderately difficult physical activity, they will not be coordinated enough to dance or even to make the tribal moves that pass for dancing these days. If their hands and the rest of their body (this is a family publication) cannot respond precisely and with grace to the input of their senses, if they cannot engage in any physical activity for longer than fifteen seconds without puffing and sweating (eewww, gross), they will not be attractive participants and sought-after partners in the carnal, lustful pleasures of the flesh which make life go around. (It's in the Bible -- 1 John, Verse 2, Chapter 16 and also, Galatians Verse 5, Chapter 19 -- look it up). Our future depends on it. Without sex, there will be no babies, and without babies there will no taxpayers to finance my wonderful pension. So, teens, get out there and play ball!

I do not want any pity, (unless pity takes the form of cash donations; Angus Cross can arrange). I have presented myself here as a motionless, stumbler. But if poor Angus has not fallen into a deep, utterly bored stupor by the end of this, and lets me publish a second half, I would like to relate several activities that I did learn in St. Lambert and which have given me a lifetime of pleasure. They came to fruition too late to do me much good, but there are a few stories which I still tell myself on long winter evenings by the fire. (Nobody else will listen.)